HDTV Production Truck

For all of you out there who work in or watch “TV” did you ever wonder who invented it? A brief, non technical history and minor Who’s who of the folks who helped couch potatoes everywhere.

Now, obviously today’s TV in all its digital high definition, PVR’d and PVP’d glory is the result of hundreds of different inventions and developments - most of them by corporate teams. But there are a few who developed the initial inventions that made the dream of Distant Vision – television possible.

As early as 1827 Sir Charles Whetstone describes image scanning and also coins the term microphone (audio, that bastard stepchild of video that makes it work) – this was 50 years before Emile Berliner actually gets around to inventing one.

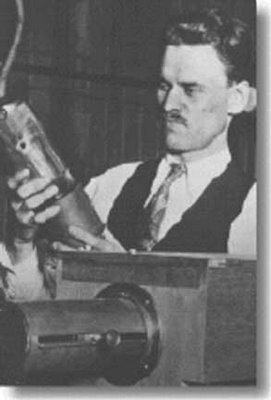

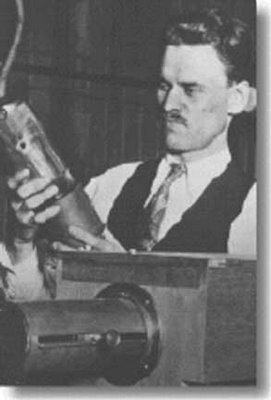

Baird & Televisior

Various mechanical devices were developed in the early 1900’s cumulating in 1925 with the Scottish inventor John Logie Baird’s Televisior producing the first recognizable face and in 1927 Herbert Hoover was the first American president to appear on “TV” – the camera is actually a mechanical device with spinning wheels and the display is square-pixel flat-panel video screen.

But arguably the one man who brought television out of the 19

th century mechanical world into the electronic 20

th century is a self taught math wiz whose work in a small lab on

Green Street in

San Francisco laid the foundation of all subsequent developments in electronic television including computer displays. Yet I’m willing to bet most readers (all three of you) have never heard the name, Philo T. Farnsworth.

This Saturday (19 August 2006) marks the 100th solar orbital anniversary of his birth

- Thanks Philo, it sure beats digging ditches!

The Mercury NewsThe definitive Philo site

Another unknown name is the man who lead the team that developed the first commercial Video Tape Recorder that is the direct ancestor of your TiVo. Yes PVR’s are a lot smaller and have a much better user interface than the 1000 above but at the basic level they are identical in the core function, that is to record and play back synchronized pictures and sound – one name from that team almost everyone will recognize even if most under 40 will think of the musician not the engineering student who worked on the team led by Charles Ginzberg

- the engineering student? Ray Dolby who goes on to found the company that bears his name and provides the audio processing that gives us “Dolby AC-3 5.1 surround sound”

- the musician? Thomas (Blinded me with Science) Dolby

And no, despite rumors to the contrary, I’m not in the picture above

article from Mercury News link above - reposted with permission

Philo Farnsworth, TV's invisible inventor, was born 100 years ago

By Frazier Moore

AP Television Writer

NEW YORK - Fish don't know they're living in water, nor do they stop to wonder where the water came from.

Humans? Not much better, as we share a world engulfed by television. And the deeper our immersion becomes, the less likely it seems we'll poke our heads above the surface and see there must have been life before someone invented TV.

That invisible someone was Philo T. Farnsworth, who was fated to live and work, then die, in sad obscurity. Now, on the centennial of his birth on Aug. 19, 1906, his invention plays an increasingly powerful role in our lives -- with less chance than ever of him being recognized.

How ironic! In this media-savvy age, not only should his name be as widely known as Bell's or Edison's, but his long, lean face with the bulbous brow should be as familiar as any pop icon's. He should be the patron saint of every couch potato. Instead, we regard TV not as a man-made contraption, but a natural resource.

Nonetheless, it was Philo Farnsworth who conducted the first successful demonstration of electronic television.

The setting: Farnsworth's modest San Francisco lab where, on Sept. 7, 1927, the 21-year-old self-taught genius transmitted the image of a horizontal line to a receiver in the next room.

It worked, just like Farnsworth had imagined as a 14-year-old Idaho farm boy and math whiz already stewing over how to send pictures, not just sound, through the air. He had been plowing a field when, with a jolt, he realized an image could be scanned by electrons the same way: row by horizontal row.

The prodigy at his plow had already made a fundamental breakthrough, charting a different course from others' ultimately doomed mechanical systems that required a spinning disk to do the scanning. Yet Farnsworth would be denied credit, fame and reward for developing the way TV works to this day.

Even TV had no time for him. His sole appearance on national television was as a mystery guest on the CBS game show ``I've Got a Secret'' in 1957. He fielded questions from the celebrity panelists as they tried in vain to guess his secret (``I invented electronic television''). For stumping them, Farnsworth took home $80 and a carton of Winston cigarettes.

In 1971, Philo Farnsworth died at age 64.

But his wife, Elma ``Pem'' Farnsworth, who had worked by her husband's side throughout his tortured career, continued fighting to gain him his rightful place in history, until her death earlier this year at 98.

Fleeting tribute was paid on the 2002 Emmy broadcast to mark TV's 75th anniversary. Introduced by host Conan O'Brien as ``the first woman ever seen on television,'' Pem Farnsworth stood in the audience for applause on her husband's behalf.

It was a skimpy challenge to the stubborn misconception that the Radio Corporation of America was behind TV's creation. This is a version of history RCA was already promulgating as its president, David Sarnoff, was plotting to crush the lonely rival who stood in his way.

Ultimately, Farnsworth would go head to head with RCA's chief television engineer, Vladimir Zworykin, and a vast company whose boss had no intention of losing either a financial windfall or eternal bragging rights. With that in mind, Sarnoff waged a war not just of engineering one-upmanship, but also dirty tricks, propaganda and endless litigation.

In 1935 the courts ruled that Farnsworth, not Zworykin, was the inventor of electronic television.

But that didn't stop Sarnoff, who courted the public by erecting a wildly popular RCA Television Pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair and, after announcing that the RCA-owned National Broadcasting Co. would expand from radio into TV, transmitted scenes from the fair to the 2,000 TV receivers throughout the city.

Thanks to Sarnoff, money woes and the lost years of World War II (which put TV broadcasting on hold), the clock ran out on Farnsworth's patents before he could profit from them.

Now, few even working in the industry that Farnsworth sparked know who he is. But one who does is Aaron Sorkin, the playwright, screenwriter and creator of ``The West Wing'' (as well as ``Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip,'' a TV drama that probes the inner workings of a fictitious TV series, which premieres next month on NBC).

A decade ago, Sorkin briefly considered scripting a Farnsworth biopic. Later on, he opted to write a screenplay that instead would focus on the battle between Farnsworth and Sarnoff.

Then he decided a play would be the better form for this tale. The result, ``The Farnsworth Invention,'' will have a workshop production at California's La Jolla Playhouse next winter, with a possible New York staging in fall 2007.

It's unlikely such a theater piece will make Philo Farnsworth a household name. But as Sorkin wrote in a recent e-mail, ``The story of the struggle between Farnsworth and Sarnoff seemed like a nice way to invoke the spirit of exploration against the broad canvas of the American Century.''

The struggle between them was fierce and unfair. But in his sad fashion, Farnsworth won: The force unleashed as television was his doing, however blind the world may be to what he did.